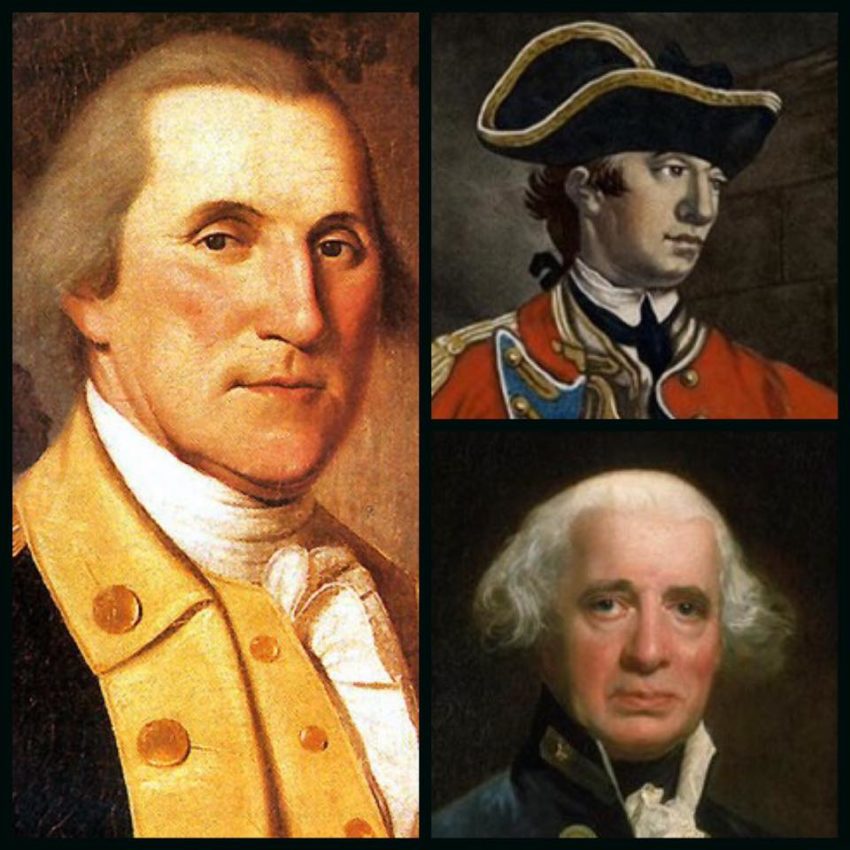

On this day in 1776, George Washington refuses to accept a letter from British Admiral Richard Howe. The admiral and his brother, General William Howe, were attempting to contact Washington without recognizing the legitimacy of his military title.

Of course, what they really meant is that they did not accept the legitimacy of the American cause.

Washington’s army was then on Long Island and in Manhattan, preparing to defend New York City from a British attack. In the meantime, Admiral Howe was moving his fleet into position and British troops were pouring onto Staten Island.

One Washington biographer notes that the British force then gathering was the “largest expeditionary force of the eighteenth century.”

Then a surprising thing happened. On July 14, a British officer came across the harbor under a flag of truce. He wanted to deliver a letter addressed to “George Washington, Esq.” Washington ordered Joseph Reed, Henry Knox, and Samuel Webb to the waterfront. They were under orders not to accept a letter unless it was addressed to Washington in his professional capacity.

Surely, they did not really think they were about to return to General Washington with a properly addressed letter.

The British lieutenant stated that he had a letter for “Mr. Washington.” Reed responded that “we have no person in our army with that address.” The lieutenant asked by what title Washington should be addressed. “You are sensible, sir,” Reed responded, “of the rank of General Washington in our army.”

The lieutenant was soon sent on his way. None of the Americans had so much as touched Howe’s letter.

A few days later, the episode was repeated. This time, a letter from General Howe was addressed to “George Washington, Esq., etc., etc.” Again, the British officer was refused.

The next day, a different British officer came over and asked if “General Washington” would accept a visit from an adjutant general to General Howe. The offer was accepted and Colonel James Paterson arrived at noon on July 20.

The two men met and were soon sitting across a table from each other.

Can you believe that Paterson threw the SAME letter out onto the middle of the table? At this juncture, Washington pointedly refused to accept—or even touch—the letter addressed to “George Washington, Esq., etc., etc.” Paterson claimed that the address “with the Addition of &c. &c. &c.—implied every thing that ought to follow.”

According to Reed’s notes, Washington retorted that “it was true the &c. &c. &c. implied every thing & they also implied any thing.” No. The letter should be addressed to him in his official capacity, or it would not be accepted.

Paterson suggested that an accommodation between the two sides should be reached, but Washington noted that Lord Howe had no authority to do anything except issue pardons. “Those who had committed no Fault,” Washington observed, “wanted no Pardon.” To the contrary, he concluded, “we were only defending what we deemed our indisputable Rights.”

Knox later wrote that Paterson looked “awe-struck, as if he was before something supernatural.”

Washington had accomplished his purpose. He had been dignified, even as he sent a message to the British.

The American fight for freedom was not going away any time soon.

h/t – Tara Ross